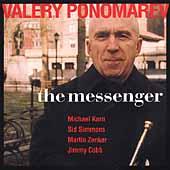

Valery Ponomarev

Here's a story done by John Berger on cool cat trumpeter Valery Ponomarev who appears on two songs on Aaron Aranita's new CD release. Pretty cool this cat.

Friday, April 30, 2004

Jazz message

Jazz messagegot to Russian

By John Berger

jberger@starbulletin.com

What would it take to get you to give up everything and follow your muse to the ends of the earth?

For Russian-born jazz trumpeter Valery Ponomarev, it was hearing the music of Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers.

"The first (player) who inspired me was Clifford Brown. When I heard that, I realized that that was the music I wanted to play, (and) there was nothing else I wanted to do in my life. Then when I heard Blakey and his band, that was it," Ponomarev explained this week by phone from New York City to help promote this year's Great Hawaii Jazz Blowout, which takes place this weekend on the grounds of Kapiolani Community College at the foot of Diamond Head.

Ponomarev (who says that Brown, Lee Morgan and Freddie Hubbard were his biggest influences in developing his own style) is scheduled to play tomorrow night at 8:45 and again at 1 p.m. on Sunday. He's also been booked for a special one-nighter at the Honolulu Club Bar 7 Lounge on Monday.

Honolulu is long way away from Moscow, where Ponomarev was born during World War II, when communist dictator Josef Stalin was at the height of his power as the all-powerful ruler of a savage totalitarian state. Ponomarev grew to adulthood in the years when Stalin's successors were officially repudiating the purges that killed far more people than the Nazi death camps. The network of communist concentration camps known as the Gulag Archipelago still held millions of prisoners, however, and expressing an interest in Western culture was dangerous.

"(Jazz) was considered purely capitalistic -- almost a propaganda device -- until the so-called Spring Thaw ... when the rulers of the Soviet Union wanted to show that we have freedom here (under communism). They even allowed jazz music, but (Russians) who practiced it were still looked upon as potential enemies of the state. That was the nature of Soviet policy and the whole regime," Ponomarev explained.

"Now, of course, there are jazz schools. But then, there was nothing like that. You had to learn everything yourself. But the nature of music is so strong that it comes through no matter what political systems or cultural background."

AFTER HEARING Blakey's band, Ponomarev decided that he was going play for the master drummer, no matter what. He spent a year studying English, mastering 20 words a day until he was reasonably fluent, and then took the risk of escaping from the Soviet Union in 1973 to pursue his dream.

"I had a feeling that, sooner or later, I would be there (in the West) with my relatives in music, so to speak. Of course it wasn't easy at all. It was dangerous. I could have ended up in jail or who knows what, but as the saying goes, 'Nothing is impossible for a willing heart.' I really needed to go, I wanted to go, and it worked out ... when you want to do something, you do it."

Several years would pass before Ponomarev would eventually meet his inspiration, and he said Blakey "was totally shocked that, from Russia, comes a young man playing in the exact style of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers."

The fit was so perfect that Ponomarev was invited to join the group, and made his reputation during the four years he was a Messenger.

Ponomarev's solo debut album, "Means of Identification," marked him as a stellar artist in his own right in 1985.

He also made his debut as an author last year with the publication of his autobiography "On the Flip Side of Sound," which he wrote in English and did a Russian translation for publication back in his home country.

He's hoping for find an American publisher for his original manuscript but, in the meantime, he has been contacted by a publisher in Istanbul who is translating it into Turkish. French and German editions are also in the planning stages.

PONOMAREV'S artistry has been documented in "Frozen In Amber," a film about the role of Russian defectors play in the performing arts in the United States, plus "Messenger from Russia," a biography that aired on the National Geographic cable TV channel.

Ponomarev feels Americans should be proud that jazz was created in this country and has now become "a cultural treasure of the whole world."

He returned to Moscow for the first time in 1990 for the city's First International Jazz Festival and has been back several times since. He says that he loves to travel -- he's already toured Turkey and Western Europe this year, and will return to Russia later in May, go to Israel and Scotland in July and August, and expects to return to Turkey before the end of the year to support the publication of the Turkish language version of his book.

Ponomarev finds great players wherever he goes.

"Wherever I come, I don't even have to look for anybody. If I'm in France, I have my French band, if I'm in Germany, I have my German band ... or if you go to one of the former East Bloc countries, there are so many great musicians there. Now the same thing in Russia. When I go to Russia, my band will be all Muscovites and all brilliant players. I wish I would have a chance to bring them to the West, so the West could see these guys."

Unlike under the days of communist rule, the problem nowadays is more financial and not political. If Ponomarev can get the financial backing for just such a tour, his fellow Russian players will be free to tour.

"A couple of years ago -- which was well after the collapse of the Soviet Union -- foreign countries were not giving visas that easily to Russian musicians, but the Russian government said, 'You want to go, go!' I was shocked the first time I heard of it. Things change. (It seemed a) hopeless situation with the Soviet regime. Nobody thought it would ever end, but it did. Now it's already 14 years ago."

© 2004 Honolulu Star-Bulletin -- http://starbulletin.com

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home